When I’m cycling to and from school with my 8 year old daughter, cars sound louder than when I cycle alone. Lorries are larger. Everything is faster. Everything more dangerous.

She cycles ahead of me on a cycle path separated from the busy road only by a dotted white line. She’s a strong cyclist for her age and proud of her ability, but sometimes she drifts towards the line, closer and closer to those cars and lorries that rush past, her tiny frame and her little black bike buffeted in their slipstream.

At least once each day, I imagine the worst. A vehicle cutting into our lane. A car hurrying out of a driveway. Or just my daughter losing balance, her feet tripping over the pedals, her bike twisting, tilting and crashing over that dotted line as a truck roars towards her.

We could drive instead. We have a 16 year old Ford Focus at home. It ain’t pretty, but it does the job. Or we could return to cycling on the footpath just like we did for her first year on the bike.

Either way, it’s not necessary for to be out here so fragile with her furiously pedaling legs, her pink runners, navy school tracksuit, hi-vis jacket and cheerfully coloured, but ultimately just polystrene helmet.

But I think ahead to her future. I imagine her having the freedom I had as a child to cycle over to a friend’s house and to school, even to eventually to cycle in and out of town. Maybe, I hope, cycling will promote resilience in her, and in some small way help her make her own way in the world when she has to.

Still, all in all, it’s clearly a small choice on my part to encourage cycling – just one of the many little choices that parents all across the world make every day. And it’s a choice made freely, one of many options available to me.

A few weeks ago I was chatting with a helpful, friendly man in his twenties as research for a book I’m writing. He was a little older than my daughter when his father was killed and his mother had to make a choice for him.

He was twelve. He didn’t agree with her decision. Going against how he was raised, he shouted at her and cried and begged, but she wouldn’t back down. She made him get into a car with his older brother. She watched the smuggler drive them away.

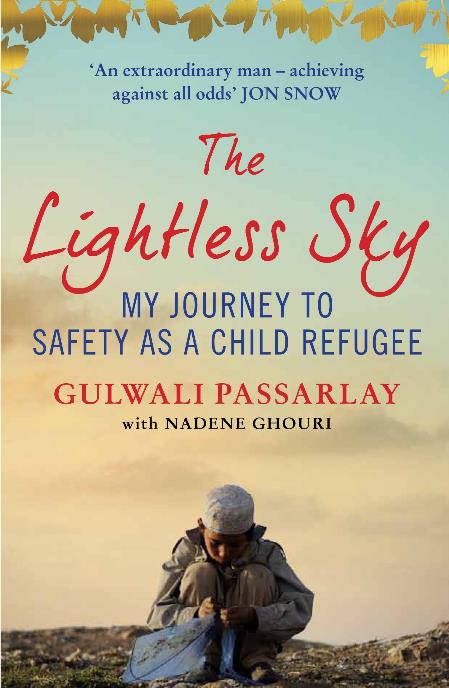

Within a day, Gulwali was separated from his brother. He traveled for a year on his own from Afghanistan to asylum and reunion with his brother in England. Even now, a grown man and a respected advocate for refugee rights and social justice, he still has nightmares about happened to him on that journey.

Despite the violence and trauma he experienced, Gulwali kept going out of pride and out of fear at what awaited him if he returned to Afghanistan. He was guided by his mother’s words to him before he left.

‘No matter how bad it gets, don’t come back.’

In a world with an unprecedented refugee crisis where 68.5 million people are forcibly displaced, parents across the world are making the harrowing choice to send their children out into the world alone, praying a better life and safety for them.

Gulwali himself remembers his mother standing tall and resolute on the side of the road until she was lost from his view. He wonders how she reacted afterwards? Did she collapse, screaming and howling at her loss? Or, more likely, did she stay quiet and lock her pain deep inside?

Right now, at this very second, a parent somewhere is making that same choice to let their child go ahead on the road without them. They’re watching their child’s fragile body tremble, buffeted by the wind, and grow smaller and smaller in the distance then disappear into an uncertain future.

Learn about the global refugee crisis with these UNHCR facts.

Learn about the human cost of the refugee crisis by reading Gulwali Passarlay’s remarkable memoir co-written with Nadene Ghouri ‘The Lightless Sky’

Really well put, mate.

LikeLike

Thanks Andy. That’s appreciated.

LikeLike