November 2016/ Photo essay / reading time: 17 minutes (4300 words + lots of photos)

It’s 1999. I’m 25 years old. I’m living in Dublin and trying to be a screenwriter. I want to have my first feature film made by the age of 26, because I’ve heard that was Tarantino’s age when he got Reservoir Dogs made. But my life’s about to change course forever.

I’ve been writing for three years and I’m getting nowhere fast. None of my ideas are working. I’ve got a script that I’ve just submitted for Film Board funding. It’s about a woman who crashes her car on purpose into hot guys’ cars to try to pick them up. It’s meant to be a romantic comedy. I don’t even like romantic comedies, but they’re popular and I want this to be the one.

I’ve lots of spare time so I’m an active volunteer with the East Timor Ireland Solidarity Campaign. It was set up in 1992 by the remarkable Tom Hyland.

I visit secondary schools for the campaign. I tell school kids that East Timor’s a tiny country north of Australia. It’s about the size of Leinster and has a population of 600,000. Its neighbour Indonesia is made up of more than 13,000 islands and has a population of 200+ million.

I tell the kids that East Timor was invaded by Indonesia in 1975 and more than 200,000 Timorese have been killed or have died by famine since the invasion. It’s grim, but I tell them things are changing. After years of international pressure, the UN will run a vote on Independence in East Timor on the 30th August.

And then out of nowhere Tom Hyland asks me if I want to go to Timor to represent the campaign for the vote?

I should be scared. I’m well aware of the atrocities the Indonesian military have committed in East Timor, but I’ve only experienced danger through movies so I imagine myself overcoming danger. I imagine standing side by side with the Timorese at the hour of crisis. I imagine returning home with great stories for screenplays and having lived a little, like Hemingway or something.

I say yes.

August

Early August. I’m at the port in Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia. I’m 12,000km from Dublin, trying to fight my way onto the Dobonsolo ferry for a three day and two night journey to East Timor.

I’m travelling with Sean Steele, a journalist and longtime volunteer for the campaign. He’s been in East Timor before and in conflict zones. We sleep on the deck with a group of East Timorese who take us under their wing. The ship’s full of Timorese returning for the vote. I speak some Indonesian and there’s few foreigners on the ship so everyone wants to speak to me. It’s exciting.

After two days, we get our first glimpse of the tiny country of East Timor. I can just about make out the large statue of Jesus on the edge of the capital Dili.

The Timorese on the ship wave flags and cheer as we arrive in port. Crowds are waiting for them.The Indonesian police carry truncheons and swing them at locals to keep them back.

Myself and Sean go to the office of an East Timorese student group in the Dili suburb of Vila Verde. The students bring us to nearby homes looking for someone who’ll let us stay with them. A few homes turn us down, fearful of Indonesian reprisals. We reach the home of Placido de Araujo and his wife, Maria. Placido’s a retired former policeman who walks with a limp from a motorcycle accident. He’s strong willed. He announces ‘You must stay here!’

There’s kids and teenagers everywhere in this house. I find out later that Placido and Maria have 14 children, loads of grand children. Also student campaigners and local kids come in at all hours to hang out and watch the news on the TV.

The house is buzzing with kids and energy. I love it here.

Myself and Sean attend UN press conferences. We meet various student groups. We do radio interviews with Irish radio stations and bring international delegations around East Timor. Everywhere we go, we’re waved to and welcomed by Timorese. There’s a sense of excitement and hope.

But the Indonesian military have ruled East Timor since 1975 and they do not want East Timor to get its freedom. A few days into our visit, a Timorese man is killed by a militia group set up, trained and armed by the Indonesian military to terrorise Timorese into voting to stay part of Indonesia. I visit the location where he was killed. There’s stones on the ground and flowers and candles where it happened.

Neighbours usher me into the house to photograph the body in a coffin in a living room. They want me to tell the world what’s happening here. I feel like a fraud, but I take the photo.

We attend his funeral in Dili’s infamous Santa Cruz cemetery. In 1991 the Indonesian military killed hundreds here which was captured in video footage that shocked the world. Now I’m here, walking where students were machine gunned down. It’s unnerving.

A few days later, I travel with student campaigners to a voter education talk they’re giving in a small village above Dili. They show sample ballots and try to combat the misinformation and fear being spread by the Indonesian military. Everyone in the village wants Independence.

Sean travels with a different student group to another voter education programme far out of Dili. I get a phonecall from him that night. The Indonesian military opened fire on his group of students. He had to hide from being shot. The next day Sean arrives back. He’s shaken, but unfazed. I hope that I’ll be like him if I’m ever in a situation like that.

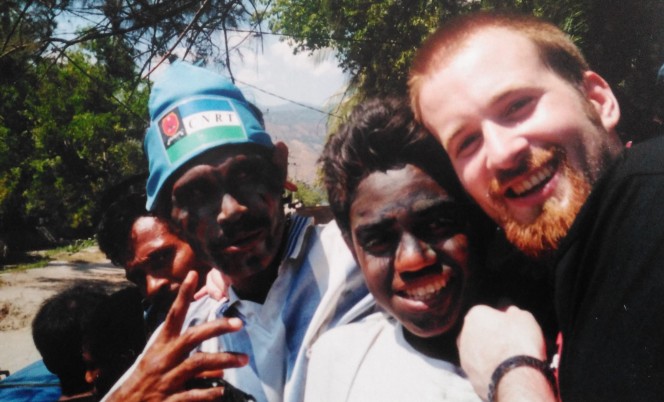

Incongruously, our next few days are like a holiday. Javier and Inacio Aja arrive. They’re brothers, supporters of East Timor and friends of ours. We go sightseeing with them to the statue of Jesus above the beach on the edge of Dili.

19th August

The vote is only 11 days away now. We attend a rally by Aitarak (Thorn) the militia set up, funded, armed and trained by the Indonesian military. They killed the man whose funeral I attended in Santa Cruz cemetery and they’ve killed many others. It’s shocking seeing them parade around with impunity.

25th August

Five days before the independence vote, we and lots of the Araujo family sit on the top of a lorry in a massive Independence rally in Dili. Our vehicle snakes through the streets for three hours. We shout ‘Mate ka moris – ukun rasik an!’ (life or death – independence) and ‘Viva Timor Leste’. My arse is killing me by the end of the rally, but I’m jubilant.

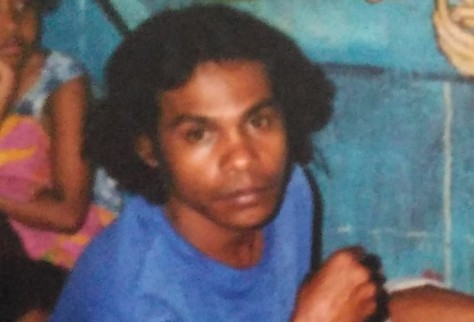

Afterwards we’re all jubilant in the Araujo home. We take loads of photos posing with the poster of Xanana, the beloved East Timorese leader, including my favorite photo of the trip. It’s of the irrepressible Toto, one of Placido and Maria’s grand children. I love his smile.

26th August

The Aitarak militia go on the warpath. I hide inside a Timorese friend’s house, my heart beating crazy fast, as gun fire goes off on the street nearby. I come out and see the windows have been shot out of an Independence group’s office. A local holds up the bullet casings to show me.

I walk down the road to the sites where two Timorese were shot and killed just minutes earlier. The bodies have already been taken away by their families. A protester holds up a sign at the site of the first murder saying it was the Indonesian riot police who did it.

At the blood stains of a second death, an American photo journalist complains that it’s getting dangerous for journalists to work here. I surprise myself by responding angrily to him, ‘It’s harder for the Timorese to live here.’

I return home to Vila Verde. Sean has witnessed militia attacks on the student offices on our street. Overall at least five people have been killed in Dili today. But despite this horror, the family go ahead with the birthday party meal and cake they’ve arranged for Sean’s birthday. It’s surreal.

28th August

All the student group offices on our street are empty now. I’m tense. Every loud noise sounds like a gunshot to me now. The Timorese are terrified of what will happen on the day of the vote. Young people are banding into groups to defend their areas of Dili from militia attacks.

None of this stops an Araujo family wedding going ahead. I go along to it and get a chance to take a photo of Placido dressed up in his finery. He looks splendid.

29th August

It’s the day before the vote. We attend a massive press conference organised by the UN. Militia leaders and Independence army leaders sit alongside each other. The Aitarak militia promise they will accept the results of the ballot.

Not everyone is convinced. We visit a group of refugees hiding out in St Joseph’s school in Dili. They’ve fled outlying districts for safety in Dili. They’ve left their homes and everything they own behind. It’s desperate.

30th August – the vote

I wake up anxious, but the city is peaceful. Placido and Maria proudly show us their voting cards and IDs before going to vote in the primary school just doors away from their home.

We’ve got a driver, but he needs to vote so he drops us off a half hour out of Dili in Hera. There’s no public transport today and people have walked long distances to get here. There’s long queues in the sun to vote, but no one minds.

We find it hard to get a lift back to Dili so end up hanging out just chatting with locals. There’s no trouble at all here. After all the build up, it’s a relaxing day, even fun.

In the afternoon after he’s voted, our driver brings us to Liquica where there’s been a lot of militia violence in recent months. We speak to UN staff and learn the vote has gone peacefully there and in most of the country. The Indonesian military’s fear tactics didn’t work as there’s been a high turnout nationally.

We know now that the result will almost definitely be independence. We’re exuberant.

But leaving Liquica, we encounter a militia vehicle. Our driver think it’s following us.He drives quickly away and runs over a piglet crossing the road. I look through the back window as we speed away. I see the piglet on its back, legs shaking in the air, writhing in pain. I can’t get that image out of my mind all night.

31st August

It’s announced that the vote results will be ready on the 5th September. The city’s tense. Fears rise in Dili as an Aitarak man killed by local gangs is buried. But the funeral goes off peacefully.

At home that night, Placido’s older kids are pessimistic. They say that Indonesia would burn East Timor to the ground rather than let it go free. I tell them that the United Nations are here now and the eyes of the world are on East Timor so that can’t happen.

1st September

Against the Araujo’s recommendations, we decide to travel out of Dili to Suai. Suai is more than four hours away and near the border with Indonesian West Timor. It’s notorious for its milita violence. We find a driver who will take us there tomorrow. He will have us back bythe 4th so that we’re in Dili when the results are announced on the 5th.

On our way back from meeting the driver, we see smoke from our taxi. Aitarak militia have attacked refugees near the UN compound and burnt down houses.

2nd September

We leave for Suai. I sit in the back of the pick up, but soon move to the front. My Indonesian is good now so I deal with our driver. Plus I’m quickly tired of being battered around in the back. Our driver is chatty. As we travel across the beautiful countryside, down rough roads and over rickety bridges, he tells me stories of the occupation. He shows me the cigarette burns on his arms from when the Indonesian army tortured him.

3rd September

We visit the Suai church. We talk briefly with the parish priest Father Hilario then spend a long time at the unfinished cathedral next to the church. Hundreds of Timorese refugees from around Suai district are sheltering here. They hope that the fact that they are on church ground will keep them safe.

In the afternoon we go on a fun trip to beach with a group of kids who are living near our little hotel.

Night. We hear on the radio that the referendum results will be announced tomorrow and not than the 5th as was previously scheduled. We have to get back to Dili before the results are announced as it’s too dangerous to be in Suai or anywhere outside Dili.

We need to leave before dawn tomorrow, but there’s a problem. We’re low on petrol and all the shops are closed. We go to a family home where they sell petrol. It’s closed, but we knock until the owner comes out. To not raise suspicions, driver tells him that my father has died and we need to leave early to get me to an airport. I walk around looking at the ground with a sad face, pretending I’m grieving.

4th September

We’re up before dawn and driving as fast as we can back to Dili in the darkness.

As the sun rises, we drive through the towns where armed militia men prowl the streets.

I’m in the front with the driver. He tells me that he had sex with one of the children that we took to the beach the other night. I don’t know if he’s serious or not. He’s disgusting, but we rely on him. He knows how to survive in Timor. He hides the film from our cameras under the bonnet of the vehicle.

About half way back to Dili, we we drive into Maubisse town. The police arrest us. They hold us in their police station. We tell them we are tourists. They are courteous, but they don’t believe us. They want IDs, but our passports are in Dili. I give them all my ID cards, including my Extravision video rental card. They note all the details down.

We are in the police station when the referendum results are announced on the TV. 78% of the population have chosen independence. The police tell us we must be happy. I feign disinterest. I say that 22% is a lot of Timorese who want to be part of Indonesia.

The police let us leave, but tell us to drive as fast as possible. Our driver get us to lie down in the back of the pickup truck hidden under tarpaulin so militia won’t see us. I lie scared and shaking as the vehicle rattles along the road. It feels like hours.

Our vehicle eventually slows and stops. I stay tense until I hear our driver’s voice saying we’re safe. We sit up. We’re in Aileu town about 45 minutes out of Dili. The driver tells us that heavily armed groups of militias drove by while we were hiding.

We join the convoy of UN staff and vehicles fleeing to Dili. I feel angry at the UN abandoning the East Timorese. I vow to stay till the bitter end.

We are reunited with the Araujo family in Vila Verde. Placido hugs me. He’s relieved that we’re alive. I’m so happy to see the family. We walk down with some of the older kids to see what’s going on in the city, but get turned back by police.

That night I sit on the roof of our house with some of Placido’s kids. I can see fires all over the city. I can’t fool myself that things are going to be alright anymore.

5th September

2am. I’m woken by gunfire. I run out to the living room. There’s a glass broken in the cabinet from a gunshot fired from the street. Lots of houses on the street have been shot up. No one’s safe anymore.

In the morning, things move quick. Placido tell us that he and the rest of the family are going to the mountains above Dili to hide. I walk back into my bedroom and close my door. I gasp as tears hit me then steady myself, wipe my eyes and go back out and say goodbye. I watch them drive away.

Sean says we need to go to the Turismo hotel where other journalists and campaigners are holing up. It’s believed to be one of the few safe places in Dili as nearly all foreigners have fled and the UN is pulling out. Walking to the Turismo, we’re passed by truck loads of militia. One of them points his gun at me as he passes. I flinch.

In the port, there’s Indonesian war ships and passenger ships. Indonesians who settled in East Timor are fleeing the country with everything they can carry. Some of the Indonesians curse at us in English. Sean mischievously waves goodbye to them.

Javier and Inacio’s leave for the airport. Their Indonesian airline flights out are today and remarkably not cancelled. We hug them goodbye.

In the Turismo hotel there’s rooms which have been abandoned by journalists in such an urgent hurry that they’ve left their clothes, their cameras, everything behind. We move into a free room.

I speak to my parents on the phone. I can tell they’re worried about me. I tell them that I should go into the mountains with the Timorese. I think that if foreigners are there, it might make the UN act quicker for East Timor. My parents quickly talk me down, but it’s not hard. I’m too scared to do anything like that anyway, but I don’t want to leave. That feels like betrayal.

Night. We have drinks, dinner here. There’s about 30 foreigners, mostly journalists or campaigners still in the hotel. Most of the staff has gone. There’s scattered sounds of gunfire in the near distance.

I take a photo that night. It’s the only photo I take the whole time in the Turismo. It’s HT Lee, a brave Malaysian photographer, and other journalists and campaigners. We’re having drinks in our room. In the eye of the storm, we’re having a laugh. What else can we do?

6th September

I’m hiding in a hotel room bathroom. Heavy machine gun fire is getting closer and closer to the hotel. Sean and Carmela Baranowska, an Australian filmmaker, are there with me as is Marie Colvin, the experienced war journalist. The foremost Australian Timor correspondent, John Martinkus, is sitting on the toilet. He is known to be on a killlist. His hands are shaking so much he’s unable to get a match to his cigarette. He sees me watching him and looks away.

We’re outside. The Turismo is being evacuated. The Indonesian army claim that they can’t protect it from the militia anymore. Sean and I have two options. We could go to the UN headquarters, but it’s filled to bursting point with refugees. The other option is evacuation to Australia. I have no idea what to do. My nerves are too frayed.

Thank God Sean has a steady head and decides we should evacuate. He says that we’ll just get in the way if we go to the UN compound. On our way to the airport with Australian consulate staff and Indonesian police, our vehicle waits for a few minutes in the grounds of a large high school. Crowds of refugees gather here. I see Julio, a student who regularly visited the Araujos in Vila Verde. I call out to him from the car. He looks at me fearfully, too scared to speak to me then slips back into the crowd.

Sean and I wait in the airport for the Australian army Hercules airplane to be ready to evacuate us and others. I can’t stop crying. Some guy I don’t know smiles at me and says it’ll be okay. I don’t know how things will ever be okay.

There’s only one East Timorese on our flight. Jacinto. He’s an Australian citizen. Otherwise we’re all foreigners.

I can see the city on fire from the airplane window.

A few hours myself and Sean are in a hotel room in Darwin. There’s a hot shower, tv, air conditioning. We have everything we need, but I can’t stop shaking everytime a door slams. I keep getting hit by fits of tears.

I think of the family. I think of Placido. I think of Julio. I think of all the people I knew over there and left behind when I got to fly away to safety. I’ve never felt pain like this before. And I hate myself because I went to East Timor looking for adventure and I found adventure. But now I’d do anything not to have it.

10th September

We’re in Jakarta for an overnight awaiting our flight back to Ireland. I go to an internet cafe. I’ve got an email from a producer. My silly romantic comedy screenplay has received Film Board funding for me to write the first few drafts.

I couldn’t give a shit.

November

More than two months later, from the deck of the Australian navy’s HMAS Jervis Bay Catamaran, I see Dili’s Christ Statue again.

Officially I’m travelling back to Timor to report to the campaign on the situation, but mostly I’m just going back to find the people I left behind. To find Placido, Maria, their children, Julio and the neighbours and students. To find out if they’re alive.

The Timorese on the ship cry as we arrive into Dili port.

I see a city that’s been systematically destroyed by the Indonesian military and their militias. Some estimates say that more than 50% of the buildings in the country were destroyed by the Indonesian military and militias. I see buildings where even the plug sockets were looted.

I travel all the way to Suai. I learn that on the 6th September, just two days after I, Sean, Javier and Inacio left Suai, a terrible atrocity took place at the church. Three priests were killed, including Father Hilario, and dozens – possibly hundreds – of refugees were slaughtered. The church is burnt down where most of the killing took place, but it’s the unfinished cathedral that haunts me. It’s empty now. There’s still blood stains in it.

But Timor is safe. The Australian army led a UN military intervention that landed on the 20th September. They Indonesian military and their militias have left. We meet the Australian soldiers all across the country. They are excited to be helping Timor and the Timorese love them.

I’m joyfully meeting Timorese I knew from before. I meet the students who were campaigning in Vila Verde. I finally I run into Julio who I last saw on the way to the airport and who had been too scared to talk with me. We hug each other. He apologises for not talking to me that day. I apologise over and over again for having put him in danger. I’m so relieved he’s alive.

But what of Placido and Maria and all the family in Vila Verde?

Just as I walk from the port towards their house, some of the older sons find me. They’re thinner, older looking, but I soon learn that Placido, Maria and all the rest of the family are alive. Thank God. In fact I arrive just in time for a Christening party they’re all attending. It’s a hectic, lively reunion just the way things always are with the Araujos.

Their home is undamaged luckily and I move back into my old room. Over the following days I keep expecting Placido and the family to show some anger at me for flying away with the other foreigners and leaving them. I feel terrible survivor’s guilt when I hear their stories.They tell me were hiding in the mountains with no food. If they came down to search for food, they got shot at. I even feel like I betrayed them by even coming to East Timor. I was there searching for an adventure during their misery.

But I soon realise it doesn’t matter to them that I left while they stayed. They are just happy I’m okay. And they don’t care why I went to East Timor in the first place. My virtuous motivation to help East Timor and my callow motivations to find some adventure, to really live, to find some good stories – none of them matter to Placido and the others.It just matters to them that I was there.

What I hadn’t realised fully was that the Araujos and the Timorese knew what they were risking. The Timorese never gave in to the Indonesian occupation even though it led to terrible suffering. They chose to vote for Independence knowing the likely repercussions. The Timorese have always taken all the greatest risks, but finally they’ve got the greatest reward – freedom.

Note: I didn’t get my film made before I turned 26 and haven’t had it made yet. I traveled back and forth between Ireland and East Timor from 2000 to 2003 while I ran a school solidarity project for the Campaign. I always stayed with Placido, Maria and their family in Vila Verde. This blog post is dedicated to Placido. He was a wonderful man. He died in 2014. I miss him.

Wow.

You learned and experienced more than expected. It is a real raw record of difficult times. Thanks for sharing.

Well done.

LikeLike

Thanks very much Olivia for taking the time to read it and for your kind comment. Much appreciated.

LikeLike

Oran, such an honest, raw and compelling account of an important time in East Timor’s and your life history, so well written, thank you for the opportunity to read it

Anita

LikeLike

Thanks so much for your comment Anita. It really was one of the seismic events in my life and obviously it’s the key event in East Timor’s history. It’s been really rewarding putting it out, particularly the response of the Araujo family and other Timorese.

LikeLike

Brilliant piece Oran. I started reading it then couldn’t put it down.

Maybe your first film should be a documentary.

LikeLike

Ha! Very kind words Rory. Much appreciated. Thrilled you liked it and even more so that it hooked you. Great stuff.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Asia. I witnessed the suffering of the Timorese when they bravely voted for Independence. (Read Out of my depth: Observing East Timor’s Independence Vote for the full […]

LikeLike